Amazing pictures of "glittering" human bodies have been released by Japanese scientists who have captured the first ever images of human "bioluminescence".

Although it has been known for many years that all living creatures produce a small amount of light as a result of chemical reactions within their cells, this is the first time light produced by humans has been captured on camera.

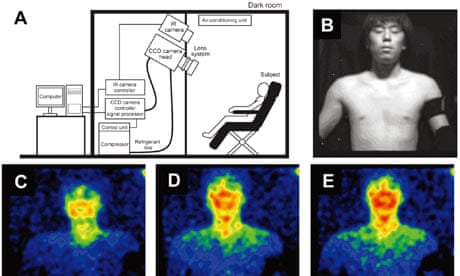

Writing in the online journal PLoS ONE, the researchers describe how they imaged volunteers' upper bodies using ultra-sensitive cameras over a period of several days. Their results show that the amount of light emitted follows a 24-hour cycle, at its highest in late afternoon and lowest late at night, and that the brightest light is emitted from the cheeks, forehead and neck.

Strangely, the areas that produced the brightest light did not correspond with the brightest areas on thermal images of the volunteers' bodies.

The light is a thousand times weaker than the human eye can perceive. At such a low level, it is unlikely to serve any evolutionary purpose in humans – though when emitted more strongly by animals such as fireflies, glow-worms and deep-sea fish, it can be used to attract mates and for illumination.

Bioluminescence is a side-effect of metabolic reactions within all creatures, the result of highly reactive free radicals produced through cell respiration interacting with free-floating lipids and proteins. The "excited" molecules that result can react with chemicals called fluorophores to emit photons.

Human bioluminescence has been suspected for years, but until now the cameras required to detect such dim light sources took over an hour to capture a single image and so were unable to measure the constantly fluctuating light from living creatures.

While the practical applications of the discovery are hard to imagine, one can't help wondering what further surprises the human body has in store for us.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion