What happens to discarded bikes from China’s sharing boom? Taxpayers pay to clear 25 million of them from bicycle graveyards

- Almost every major city in China had a ‘bicycle graveyard’, where hundreds of thousands of disused bicycles were stacked up after their operators went bankrupt

- The pathway from street corners to disassembly mills is filled with legal entanglement between local governments, bike companies, and recycle factories

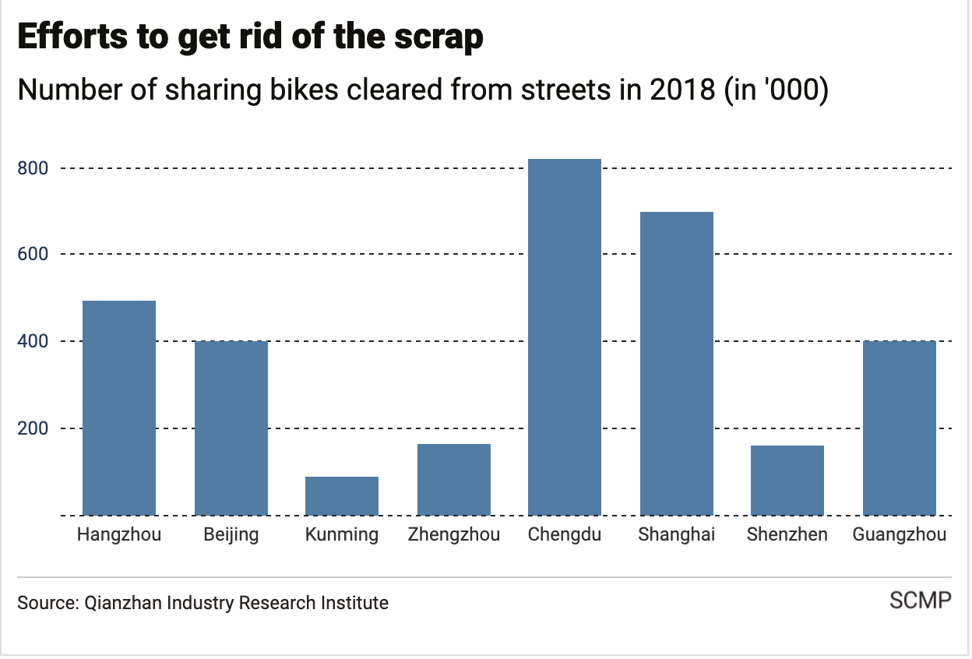

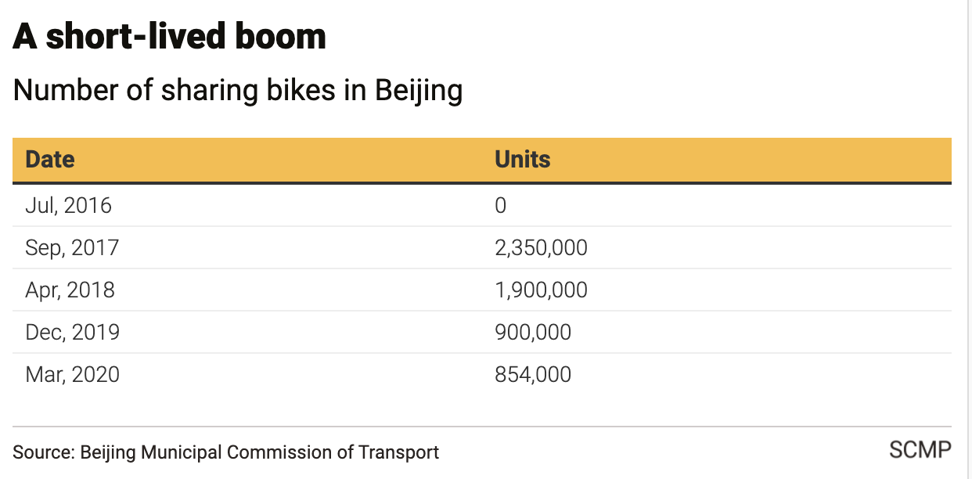

Three years after China’s blooming bike-sharing economy wilted, local authorities are about to send the last of 25 million abandoned bicycles to recycling plants, pruning the remaining blight on cityscapes left behind by dozens of companies that have gone bust.

All the disused bicycles must be scrapped by the year’s end under a compulsory retirement scheme imposed by city councils to ensure safety. The costs of taking them off the streets and the bicycle graveyards are borne by taxpayers, as all but three remain from a crop of as many as 70 bike-sharing companies, each plying China’s streets with a different brightly coloured vehicle.

Ofo – the three alphabets resemble a rider on a two-wheeled vehicle – grew out of that idea, becoming the first to let commuters rent a ride for as little as 1 yuan, with the freedom to pick it up or drop it off anywhere, helped by the convenience of a smartphone app.

It did not take before the drop-anywhere business model became a public nuisance, as pavements, footpath, parks, and every inch of public space became dumping ground for idle bicycles.

A relentless price war on the rental fees, down to as little as 0.1 yuan increased the cash burn for bike-rental companies and drained resources, even as most of them struggled to find a way of turning a profit.

Alibaba owns South China Morning Post.

What happens to the bicycles, between 25 million and 30 million of them, piled into mountains around the country and left to rust when their operators go bust?

“Shared bikes can never be reused or resold as a second-hand commodity,” said Zhu Qi, a manager at China Recycling Resources, a state-owned recycler in Beijing. “Scrapping, dismantling and recycling are basically the only way out for them.”

Some small recyclers are going after specific parts of the bicycle, like the rubber tires, resorting to advertising in Baidu Tieba and other online forum sites to seek out abandoned units.

“In terms of the capacity of the recycling industry in China, processing all the abandoned bikes is not that much of a problem,” said Zhang. “The trickiest obstacle is the property rights of the bikes ... The number of bicycles being scrapped runs in the tens of millions.”

Legally, bike-sharing companies own their products and are responsible for their disposal. But since most of them have gone bankrupt, cleaning up is the last of their concerns.

That burden falls to local authorities. The city council of Dongguan in southern China’s manufacturing hub of Guangdong province, spent 1 million yuan of taxpayers’ money clearing tens of thousands of abandoned bicycles from its streets last year at a cost of 8 yuan per vehicle, according to a tender document.

“Now the peak of recycling sharing bikes has passed,” Zhu said. “Bike companies have stopped burning money and putting piles of bikes on the streets, and they are gradually replaced by electric ones.”